I am super excited to be kicking the year off with a fantastic dive into the juxtaposition of India Stack vs Open Banking. This piece is a collaboration with Manjot Pahwa, Stripe’s India Head and an OnDeck Fintech Fellow.

Thank you to all those who provided their thoughts and feedback throughout the process!

This week’s post is a long one so make yourself a fresh brew and dive in. I hope you enjoy and I know opinions on this topic are strong so please reach out with your feedback and comments.

Summary

Open Banking as a concept was born in Europe in the mid 2010’s but rapidly spread throughout the world in various guises. It promised innovation and competition within the financial sector as well as greater consumer control of their data, in line with where Europe had been moving with data privacy (i.e. GDPR). However while it was heralded as a step change for a traditionally slow moving industry, it has not yet lived up to its expectations but we are optimistic that the full potential of PSD2 can be unlocked to include greater interoperability and an expansion of faster payments. Compared to India Stack, Open banking was limited in its scope and, in its raw form, a legal framework which different countries have interpreted in non-uniform ways, thus resulting in a slower pace of adoption and innovation. We would encourage policymakers to be more prescriptive in what data must be provided as well as to create incentives for banks to continue to innovate. Despite its shortcomings, the talk of “open finance” and the implementation of new initiatives like variable recurring payments (VRP) show potential for what it could become but in terms of a comprehensive approach to innovation, we should look 6,500km east., to India.

India has leapfrogged most other countries' payments systems through its comprehensive innovation of digital infrastructure which started at the centre of financial services, the identity layer. “India Stack” had greater ambitions than that of Europe because India’s financial system was in need of a larger overhaul and it has been much more successful. Innovation has greatly increased and consumers have a mechanism for user consent to improve data privacy. Its foundational support for a new digital identity infrastructure layer is the key piece of the puzzle that has also drastically widened access to financial services.

Ultimately, both Europe and India had different ambitions going into their respective initiatives, which underpins their relative successes. At the turn of the century, India needed to overhaul its informal economy with a centralised database of citizens for identity and national security purposes as well as establishing official country statistics. This led to the beginning of a new national identity system which would bring greater structure around data privacy, inclusion and innovation. It has seen a dramatic positive impact from its ambitious plans as well as seeing copycats around the world. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery. Europe on the other hand had more modest goals, coming from a much more developed starting point, and has not yet achieved them but has shown some promising signs.

Background

Open Banking

Open Banking is both a global concept but also the name given to the UK’s implementation of the European PSD2 legislation which came into force in January 2018 and focuses narrowly on payments within Europe. For the purpose of this report, we will use open banking generically to refer to PSD2 powered innovation in financial services in Europe.The original impetus behind OB was to promote competition with the banks, improve efficiency and consumer choice as well as to foster greater innovation by unlocking consumer data from large banks and allowing new players to build on top of it. Additionally, across Europe, it was designed to create a more integrated financial market with a focus on making transactions faster and safer by breaking up the monopolies of banks and payment processors and allowing innovation. Prior to PSD2, there were some fintech’s that were using screen scraping to provide services to consumers which banks tried to block. Once the EU looked at these TPP’s in greater detail, they realised the need to “control” them but also to give consumers choice and access to their data.

Before OB, large banks did not face much competition because they locked up consumer’s information and didn’t provide access to it. The difficulties of switching bank accounts was relatively high and consumers lacked any meaningful way to access their own data that banks held. Under OB, banks were forced to allow access and control of customers’ personal and financial data to third-party providers (TPP), which are typically tech startups and online financial service vendors. Customers give consent to a TPP to access their data at the underlying bank through checking a box on a terms-of-service screen in an online app. The TPP’s APIs can then use the customer's shared data to build innovative products and services for their benefit. Use cases might include comparing the customer's accounts and transaction history to a range of financial service options, aggregating data across participating financial institutions and customers to create marketing profiles, or making new transactions and account changes on the customer's behalf.

Whilst PSD2 regulates what needs to happen in a legal framework, focusing on forcing banks to open up access, it provides no framework or guide as to how it happens which has resulted in different implementation standards across the region and amongst banks which is part of the reason innovation has stifled. For example, banks have each implemented different customer authentication elements and have different levels of API service which means there is no unified customer journey, it differs from bank to bank.

India stack

Over the past ten years, India has seen an ambitious overhaul of its digital infrastructure through the development of the India Stack. The main objectives of this initiative have been to promote financial inclusion through increased access to financial services, improve the delivery of public services and benefits, and increase competition in the Indian financial sector. It’s the comprehensiveness of the India stack that has enabled the rebuilding of the India economy.

.

The current India stack has a couple of layers to enable these achievements. These systems include digital identity or Aadhaar, interoperable low cost payments powered by UPI, and consent based data sharing models aka Account Aggregators.

Layer 1: Aadhaar or unified digital identity across all services

The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) is a statutory authority established under the provisions of the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016 (“Aadhaar Act 2016”) on 12 July 2016 by the Government of India under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. The UIDAI is the custodian of all the information collected for the Aadhaar identity scheme. It provides identification services of Aadhaar holders. In turn, it is subject to extensive regulation requiring it to protect individuals’ privacy, particularly by ensuring the security of their core biometric data.

The Aadhaar identification system, launched in 2010 by the UIDAI, is a digital identity infrastructure with a very low unit cost of operations, to which all residents of India are entitled. Individuals apply voluntarily for an identification number which is linked at the time of enrollment to their biometric identifiers such as photograph, ten fingerprints, and two iris scans—as well as basic demographic data. The UIDAI facilitates the collection of demographic and biometric data during Aadhaar enrollment, verifies its uniqueness, and stores the information on a central identity repository. Approximately ~1.2 billion Indians have already been enrolled into the Aadhaar database.

Aadhaar had faced a lot of opposition and scepticism initially due to serious privacy concerns. While the government was trying to mandate Aadhaar for every social service, the Supreme Court ruled out that possessing an Aadhaar is “voluntary and not mandatory” in a judgement on 23rd September 2013. On 24th August 2017, the Supreme Court unanimously agreed on the fundamental right to privacy.

The technology that enabled Aadhaar as a foundational identity for a digital ecosystem involves APIs which allow public and private service providers to authenticate identity using the underlying data biometrics, demographics, links to individual phones registered with Aadhaar to facilitate authentication by means of a One Time Password (OTP). Using these technologies, the launch of the digital ID (Aadhaar number) was immediately followed by its linking with several public sector services, including banking services, which encouraged further adoption.

Layer 2: Interoperable payments via UPI

One of the key objectives of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been to provision affordable financial services to help achieve the goal of financial inclusion. This led to the inception of the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), as a retail payments and settlements systems operator, overseen by the RBI in its role as a regulator of the national payments system.

The growth of mobile payments and the incorporation of its service providers into the formal banking system was accompanied by a re-think of the payments infrastructure in India. Based on the Aadhaar foundational ID, the NPCI began to offer the choice of linking a person’s debit card to their Aadhaar identity. Prior to this, the use of credit and debit cards in India was very low with approximately 20 million credit cards in the country and only two million digital payment acceptance points, such that in effect, many features of card-based payment systems were inaccessible to the larger population. United Payment Interface (UPI) is an interoperable payment system developed by the NPCI. UPI is a payment system that powers direct and instantaneous settlement across multiple bank accounts for both peer-to-peer and peer-to-merchant use cases with seamless fund routing. India’s digital transaction growth has been explosive, already surpassing the US and China

This innovation was also central to India’s ambitious financial inclusion initiative, the Jan Dhan Yojna (JDY), where each of the new accounts created were accompanied by an Aadhaar linked “Rupay” debit card. By 2011, the NPCI launched the Aadhaar Payments Bridge (APB) and the Aadhaar Enabled Payments System (AEPS), which use the Aadhaar ID number as a central key for channelling government benefits and subsidies electronically to the intended beneficiary’s bank account.

Among all the local payment methods in India, UPI is the most popular one and shows no signs of slowing down. Since its launch in 2016, UPI has grown exponentially at a CAGR of 414%, clocking an all-time high of 2.3 billion transactions in January 2021. With new use cases around UPI (such as recurring and credit on UPI) and growth in person-to-merchant (P2M) transactions, we expect it to see continued growth. To prevent monopolies, the NPCI capped market share for UPI apps at 30% although existing players have two years to comply. The current market share for UPI is shown below. Primary drivers for this growth of UPI payments is the focus on low cost for the merchants and seamless user experience for the end customer compared to cash based payment methods. RuPay is a government mandated Local Payment Method but a minor one compared to UPI and wallets. Both UPI and RuPay have zero MDR, so lots of Payment Aggregators / Payment Gateways lose money on these two payment methods and make up for it in Payment methods like credit cards and other software solutions.

Source: Economic Times India

Layer 3: Consent based sharing of data through Account Aggregator framework

After the UPI payment system took the payments ecosystem by storm and to reinforce the goal of financial inclusion in an equitable manner, the NPCI introduced the Account Aggregator framework. The idea is to enable innovation on top of a consistent consent based data platform. The Account Aggregator framework introduces consent based encrypted data sharing on an individual and business basis. This allows individuals and businesses to share their data which might be spread across multiple services and bank accounts. Similar to Non Banking Financial Corporation (NBFCs), account aggregators are also regulated by the RBI. Several companies have been given in-principle approval to get started. Account Aggregators cannot see, store, or resell the data in order to protect the end consumer. Consent is programmable, can be one-time or a time limit based consent. A specific example of this user flow is a user can grant access to their data for a one-time use with a loan provider in order to give a better risk rating.

Open Banking stack

Unlike the expansive India stack which began with a digital identity, a key component of any forward-thinking payments and financial services stack, Open Banking in Europe was a small part of a wider shift to create a single digital financial market in Europe. It is a common legal framework setting out customers' rights to allow third parties access to their bank account data and to initiate payments from their accounts. There is no central digital identity foundation that private and public institutions can use to verify identity although recent announcements after COVID suggest that this is coming with the new European Digital Identity (EDI) which looks on the face of it to be similar to Aadhaar, just 10 years later.

Whilst details on EDI are scarce, there has been talk around linking it with financial services which would seek to mimic the interoperability of UPI but the path of this and timeline is unclear. Payments in Europe are already low cost due to regulation limiting interchange charges by card networks to 0.2%-0.3%, although with Brexit, card networks are seeking to increase UK to Europe interchange by 5x. Account to account (A2A) payments are one innovation that has been enabled by the PSD2 directive which are real-time and free to consumers and becoming more common for businesses due to their low cost. In the UK this is through Faster Payments and across Europe it is via SEPA. The infrastructure to build out this functionality for B2C use-cases is only in its early phase. So while the OB stack is less comprehensive, the existing payments infrastructure across Europe was more developed than India’s pre-UPI and is already broadly accessible and low cost. Open banking is constrained by the PSD2 legal framework which is the reason for its more limited scope but any expansion into open finance would sit on top of the PSD2 framework in its own right and could be more broad.

Comparison of the two models

Promotion of innovation within financial services for better services to citizens

Innovation is challenging to quantify but it is clear from the rapid adoption of the layers of India Stack, it has successfully achieved its goal of increasing innovation. India has continued to build upon the initial layers with new innovations such as the aforementioned Account Aggregator framework and also its new Open Credit Enablement Network, a set of frameworks and protocols focused on opening up access to credit. True innovation in India has far outpaced that as a result of Open Banking, whose impact has been more muted to date. The Open Banking concept is still not well understood among consumers and use cases still largely centre around personal finances and payments (by design given the limited scope of PSD2). Both India and Europe have succeeded in providing access to financial information spread across multiple institutions levels the playing field for new entrants which may not have the data advantages the larger banks enjoy. Moreover, the India stack enables access to financial information for the widest array of data subjects including consumers and small businesses.

Data safety and privacy

The access model for data differs significantly for the two systems. Jurisdictions such as the EU have General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules which banks and the entities handling the customer data are subject to. The fintechs that build on top of this get access to an extensive amount of data for many users and then are subject to various compliance around protection of that data. The overlap of GDPR and PSD2 has increased the compliance burden but does provide innovation for fintechs to provide data protections as part of their product offering so third parties don’t have to think about the regulatory and compliance elements. These data privacy regulations are becoming increasingly important when the opening up of access to data by authorised and permissioned third parties to make sure it is not used for unintended purposes.

India’s data flow model is based on consent of the user rather than compliances. The entity that wants an account aggregator licence and acts as the financial data Account Aggregator on top of the India stack is responsible for handling the customer’s data, rights and obtaining consent. Data is brokered through the fintech on a per user basis from the underlying financial infrastructure. India itself has taken steps to create a data privacy framework through the Personal Data Protection Bill (PDP) although the bill has yet to be passed.

The introduction and regulation of data fiduciaries (referred to and regulated as “account aggregators” in India) could reduce some of the risks to privacy and identity theft that may in principle arise from the more widespread sharing of data envisaged in other open-banking applications.

Central Identity tying them all

In India, digital identity tied to basics like biometrics has been an integral part in delivering efficient KYC for more than a billion people. Several tenets of UPI such as interoperability, 0 MDR fees and the lack of the need for a smartphone has unlocked access to digital financial services for a large number of previously unbanked Indian users. Operationalization of consent in the India model was only possible through the notion of a single identity for every user. The presence of a single identity reinforces trust that the data being obtained is only for the user.

This is one area, as mentioned before, that Open Banking wasn’t designed to tackle but it appears that with Europe’s Digital Decade initiative, digital identity is on the roadmap and provided access is open and developer friendly with easy to use APIs, should form a great foundation for future innovation in financial services across Europe. Identity is the first problem to tackle and will provide a foundation for subsequent services to be built upon, much like what happened in India.

Financial inclusion

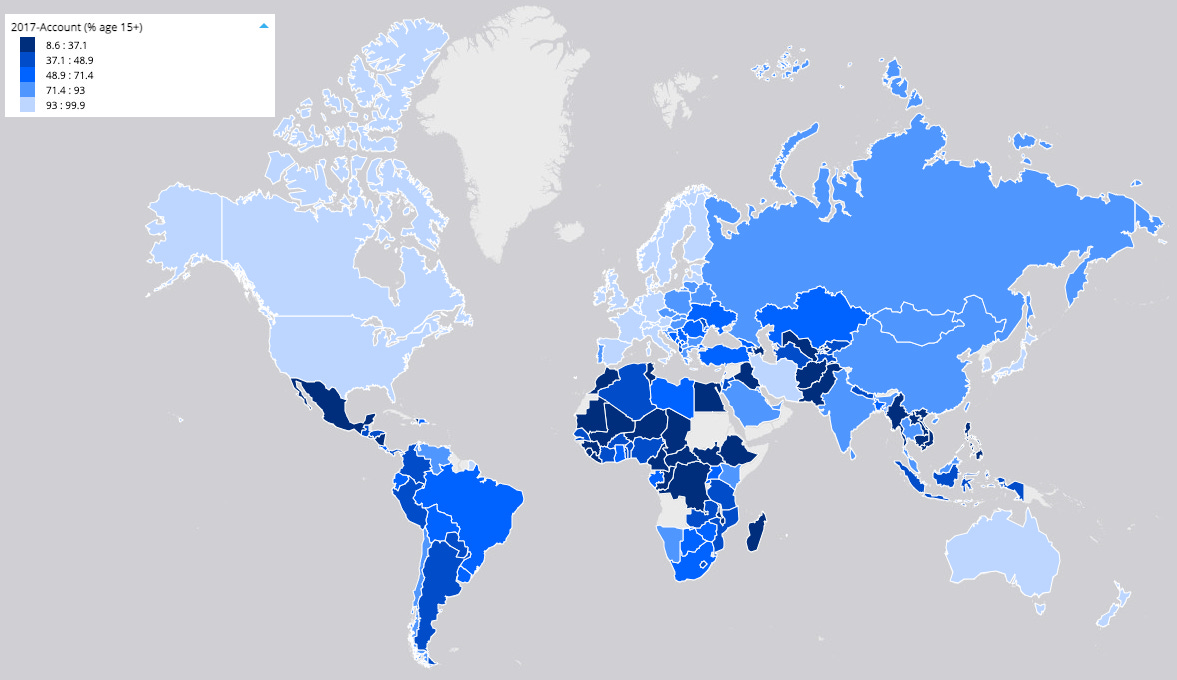

As the graph above shows, financial inclusion (as measured by % of bank accounts for 15 year olds and older) varies across countries and continents and so it is difficult to make sweeping declarations of inclusion. However, it is clear that Europeans are more included in the financial system than those in Asia although there is some disparity between Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

The India Stack is widening access to financial services in an economy where retail transactions are heavily cash based, even till this date, ~89% of the total transactions in the country are in cash. Until recently, a large share of India’s population lacked access to formal banking services and was largely reliant on cash for financial transactions. The expansion of interoperable mobile-based financial services and payments that enable seamless ways to conduct financial transactions has provided a necessary fillip to the digital economy. The government recently also launched a voucher based payment mechanism e-RUPI to efficiently distribute benefits to the people in a targeted manner. Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) is the Modi government’s flagship financial inclusion program. Launched in August 2014, it continued a tradition of bank-led financial inclusion programming in India. About ~80% of Indians now have bank accounts. By 2017, 79% of the rural population had bank accounts versus 76% for urban Indians. The gender gap in financial access has also closed in recent years. According to Global Findex data 8, the gap between account access for men and for women closed from 20% (63% for men vs 43% for women) in 2014 to just 6% (83% vs 77%) in 2017.

As discussed earlier, financial inclusion wasn’t a specific goal of OB and the PSD2 directive in Europe but was always in mind and any changes would be a positive side effect. Widespread economic disparities have caused societal issues in the past in Europe and policymakers always have a keen eye on it but the extent of exclusion was not as high as in India which could be why the version of open banking that was proposed and implemented wasn't anywhere near as comprehensive as we describe above with “India Stack”.

In one fell swoop India has leaped ahead of the EU with its end to end digital infrastructure developments which has now been copied in Brazil, with the EU recognising the merits of such a system and announcing plans of its own for a digital identity in June 2021 (also partly a response to Covid) and a new payments infrastructure (EPI). We shall see how and when either of these two copycat services come online. Another key advantage India has is that it is one, albeit very large country, whose government stepped out of the way of the private sector when constructing “India Stack” which is one of the reasons for its success. Aadhaar was created by entrepreneur Nandan Nilekani under the purview of UIDAI and now under the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. Europe on the other hand is a collection of nearly 30 different countries, each wanting to maintain or increase their own sovereign political and economical power which makes continent-wide initiatives more difficult. Notably EPI is also more designed towards thwarting the large foreign companies that dominate the European payments space and not to provide new innovation or data privacy for citizens.

What does the future look like?

For Europe, the future is full of potential. Whilst open banking was hailed as a revolutionary change for the financial sector, incumbents, who still hold a lot of power, were left out and forced to provide access and resources with little benefit to themselves which has meant they have dragged their feet and put up roadblocks. We have seen a number of new use-cases building on top of newly opened data access but a must-have use case has still yet to be found. A number of surveys point to companies looking to integrate open banking in the near future, which is positive, but will tomorrow come? Outside of the UK and a few other markets, open banking penetration is still low and across Europe in general, it is relatively unknown (28% of consumers have “no idea” what it is according to Ecommpay).

While it is still early for open banking, there is already a lot of chatter about broadening the scope to become “open finance” with much broader data sharing beyond payment accounts being discussed. Coupled with the recent emergence of Payment Initiation, the ability to authorise a payment directly from your bank account without leaving the merchant page, could create more innovative end user experiences and products. Open Finance would bring a wider range of financial products and services under its purview giving consumers even more control over their data and hopefully engaging them further with their finances and empower them to make better decisions. As an example, budgeting and personal financial management services would have a more holistic picture of a consumer’s financial life because they could be integrated with not only payment accounts but also mortgage accounts, investment accounts and pensions.

What must come first though is building out digital infrastructure to support open finance like India has done with Aadhaar (and later Open Credit Enablement Network, OCEN) and make it interoperable so third parties can leverage its eventual ubiquity. A siloed, government only identity product will not work but government backing and support would most certainly be needed to gain widespread private sector adoptionAn interoperable digital identity service will provide a foundation for future compatibility between wallets and hopefully provide some competition for any walled gardens that tech giants might have their eyes on.

We are still in the first innings of open banking and we are excited for the innovation still to be built and whilst India has jumped out to a significant lead, the future is still unwritten and the most exciting elements are yet to come.

Your feedback is a gift, please give below 🙏

Good || Bad || Needs Improving

See you soon!

amazing analysis of the fintech stack in India and europe 👏🏻